History of the National Anthem: Is “The Star-Spangled Banner” Racist?

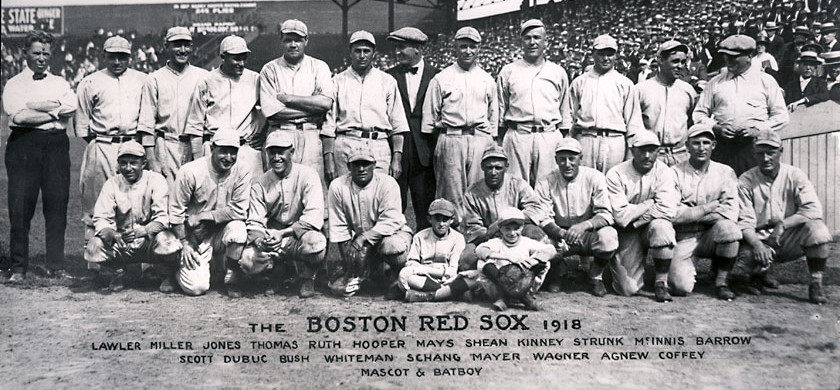

Visitors to the National Museum of American History in 1989 look up at the Star-Spangled Banner. Source: Smithsonian, “The Star-Spangled Banner: National Treasure,” si.edu (accessed Oct. 18, 2017) The controversy over NFL players and others protesting while the national anthem is played has raised questions about the history of “The Star-Spangled Banner” itself, as well as whether the anthem is racist because of three lines in its little-known third verse. Inspiration behind the Anthem The US national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” was written during the War of 1812 by Francis Scott Key, an American lawyer and poet. In 1814, Key was aboard the British ship Tonnant negotiating the release of Dr. William Beanes, an American civilian and friend of Key’s who was imprisoned by the British for allegedly aiding the arrest of British soldiers. While on the ship, Key witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland. Key was detained on the ship during the attack and was inspired to write a poem on Sep. 14, the morning after, upon seeing an oversized American flag flying intact over the fort and realizing the Americans had stopped the British advance. [1][2] During the attack a 17-by-25 foot storm flag was flown. The flag Key saw after the attack was a 30-by-42 foot garrison flag (a flag for troops) commissioned by Major George Armistead in order “to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.” The flag was sewn by Mary Pickersgill (assisted by her daughter, two nieces, and an indentured servant), and contained 15 stars that are 24 inches from point-to-point. Today the flag is on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. [3][4] The Lyrics The original poem contains four verses: O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep And where is that band who so vauntingly swore, O thus be it ever when freemen shall stand Publication of the Anthem Once back in Baltimore, Key gave the lyrics to his brother-in-law, Judge Joseph H. Nicholson, whose wife Eliza had a 12-year-old local printer’s apprentice, Samuel Sands, issue the poem, now titled “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” as a hand bill on Sep. 20, 1814. By the middle of Oct. 1814, at least 19 papers had published the poem and it had been renamed “The Star-Spangled Banner” by the Baltimore Patriot. The poem was then set to the music of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a popular British drinking song composed by John Stafford Smith. The idea to do so is credited variously to Key, Nicholson, and actor Ferdinand Durang, the latter of whom allegedly first performed the song in public at Captain McCauley’s tavern in Baltimore in Oct. 1814. [1][4][5][6] How Baseball Started a National Tradition In 1889, the US Navy adopted the song for official use and in 1916 President Woodrow Wilson ordered the song played during official military events. There are records of “The Star-Spangled Banner” being played at baseball games as far back as 1897. However, the song came into prominence for use at sporting events during the seventh-inning stretch of game one of the 1918 World Series in Chicago between the Chicago Cubs and the Boston Red Sox. As reported by the New York Times on Sep. 6, 1918, Jackie Fred Thomas, Red Sox third baseman who was on leave from the Navy, stood and saluted the flag during the anthem, and other players followed suit while the crowd sang along. For the fourth game, the series was in Boston and owner Harry Frazee, a Broadway producer better known for trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees in 1920, decided to have the anthem performed before the start of the game, beginning the tradition we know today. The anthem was played before almost every baseball game after World War II, when sound systems were widely available and the teams did not have to incur the costs of hiring a band. The practice spread to other sports and events. [7][8][9][10][11]

On Mar. 3, 1931, President Herbert Hoover signed a bill making “The Star-Spangled Banner” the official national anthem of the United States. The bill, introduced by Representative John Linthicum (D-MD) on Apr. 15, 1929, was supported by more than five million individual signatures and letters from 150 organizations. Detractors of the bill were concerned that the song was too difficult for the vocal range of most Americans. As currently stated in 36 US Code § 301, when the anthem is played people should stand with their right hand over the heart and men who are not in uniform should remove their hats and hold it over their hearts. Members of the military in or out of uniform should give the military salute and “maintain that position until the last note.” If the flag is also displayed while the anthem is playing, everyone should face the flag. [12][13] Is the Anthem Racist? As the debate about protesting during the national anthem has gained more attention, the issue of whether the national anthem is racist has been raised. The version of the anthem sung today is only the first verse of the four-verse song. The third verse includes the lyrics: “Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution / No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave.” As the debate about protesting during the national anthem has gained more attention, the issue of whether the national anthem is racist has been raised. [1][14][15][16] Some historians believe that the third verse celebrates the defeat and deaths of the Corps of Colonial Marines, which was one of two units of black American slaves fighting for the British (in exchange for their freedom) during the War of 1812. They point out that we have to consider the context: Key was against abolishing slavery, he owned slaves, and he referred to black people as “a distinct and inferior race of people.” Jason Johnson, PhD, Associate Professor of Journalism at Morgan State University, stated that Key was “not against slavery; he just thought that since blacks were mentally inferior, masters should treat them with more Christian kindness. He supported sending free blacks (not slaves) back to Africa and, with a few exceptions, was about as pro-slavery, anti-black and anti-abolitionist as you could get at the time… Key was saying that the blood of all the former slaves and ‘hirelings’ on the battlefield will wash away the pollution of the British invaders… ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ is as much a patriotic song as it is a diss track to black people who had the audacity to fight for their freedom.” On Sep. 13, 2017, a statue of Francis Scott Key in downtown Baltimore was covered in red paint with the words “racist anthem” painted in black. [17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] Other commentators note that Key could have been writing about white people conscripted by the British, and say that we can’t know for sure what his thought process was. They point out that Key sometimes defended slaves in court and fought against slave trafficking. Mark Clague, PhD, Associate Professor of Musicology at the University of Michigan, stated, “The social context of the song comes from the age of slavery, but the song itself isn’t about slavery, and it doesn’t treat whites differently from blacks. The reference to slaves is about the use, and in some sense the manipulation, of black Americans to fight for the British, with the promise of freedom. The American forces included African-Americans as well as whites. The term ‘freemen,’ whose heroism is celebrated in the fourth stanza, would have encompassed both.” [14][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

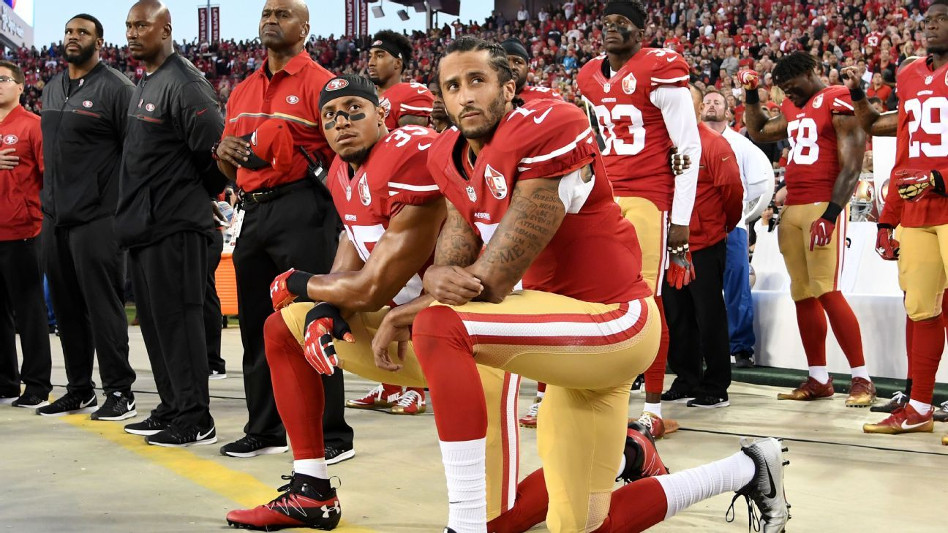

The practice of having NFL players on the field during the national anthem before every game began in 2009; prior to that, players were usually present only on special occasions such as Super Bowls and 9/11 tributes. [27] After San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick decided to kneel during the anthem in 2016, he said, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.” The 49ers released a statement about his decision to protest, saying that the national anthem “is an opportunity to honor our country and reflect on the great liberties we are afforded as its citizens. In respecting such American principles as freedom of religion and freedom of expression, we recognize the right of an individual to choose and participate, or not, in our celebration of the national anthem.” [26] While NFL players and other athletes taking a knee during the anthem are not protesting the anthem itself, the history and possible racism of the lyrics provide another layer to the protests. |

|||

|

Footnotes:

|